I was looking for something to read on a clear, milky morning in early spring. I’m spoilt for choice when it comes to books – my office drowns in them, and when I move the heaps from place to place, I rediscover thoughts I had at the time of buying then; what I hoped to learn when I carried each one to the till. It’s no failure to realise that I haven’t read most of my books yet. Gathering them around me provides a map of where I thought and what I wondered at the time. I’m sure they will become something new when I read them at last, but they will not be nothing until then.

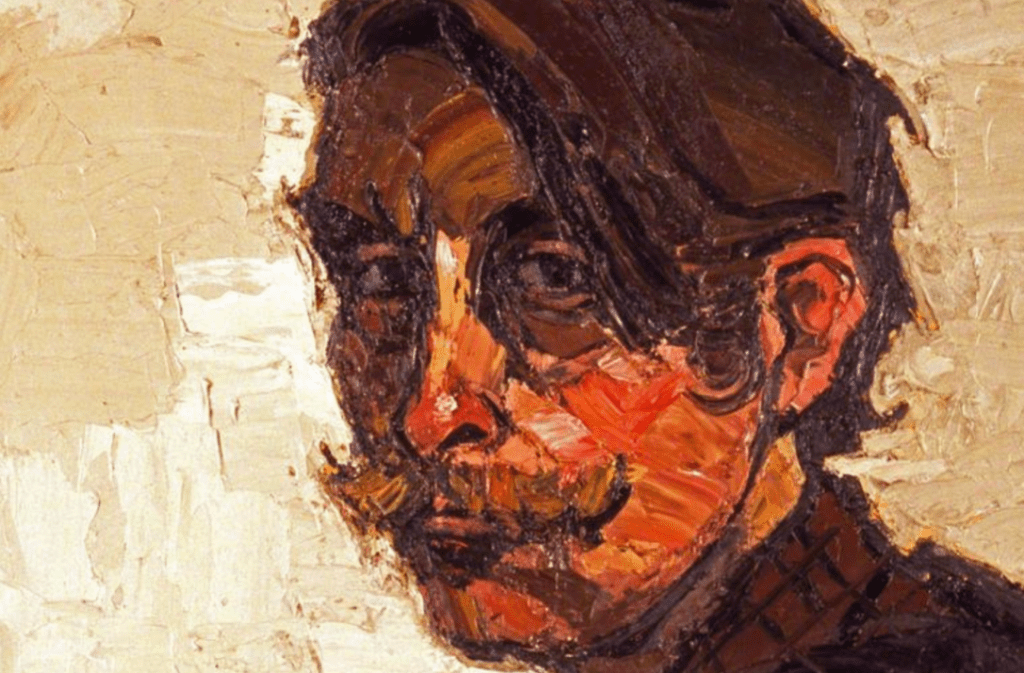

Almost at random, I chose Across The Straits, the autobiography of the artist Sir John Kyffin Williams. As my focus tightens around Wales, I can’t ignore this man. I found a gallery devoted to his work at Oriel Ynys Môn at Llangefni, and I loved it all. Alongside angular portraits and stark scenes of London churches, Williams rushed into view as a man commemorating a peopled landscape of North Wales; a fading idyll of rough farmers and hard living. He felt like the artistic equivalent of RS Thomas, and of course I was thrilled to realise that the two men overlapped, preoccupied by comparable strands of nationality, culture and belonging. In the aftermath of that exhibition, I found that Williams had become a place in my imagination. I visited the idea of him in certain moods when I felt like ponies or treeless farm buildings – a clean, cold wind across angular mountains.

Across the Straits is no great work of literature. It’s gentle and eccentric, and the details are only partially relevant to a visitor like me. Even at my best, I’m not used to reading Welsh placenames. I take a mental image of their approximate shape and length, then I file them according to their first and final letters. After a while, I ignore them altogether, just as I ignore the many connections and ancestries which lie behind David Kyffin Williams. He’s entitled to make certain claims of aristocracy – at the start of the book, there’s even a family tree, but this was meaningless to me. Instead, I blurred my vision and allowed the stories and fragments to build in heaps around certain features of landscape and geography. The accumulative impact is impressively indigenous, but he almost knows too much of his ancestry.

Like the hill farmers in RS Thomas’s poetry, the shepherds depicted in Williams’ paintings are famously primordial; they’re nameless replicants hewn from the national fabric like rocks. But Williams’ family history is busy with fact and anecdote which reaches far back into Welsh history. He’s an aristocrat, and yet he would speak for those sons of the soil. That’s a fascinating dynamic, because who is really entitled to speak for whom?

The book flares into life in a series of sporting vignettes. Williams was a hunting man, but his sport is only of peripheral interest here. Woodcock and hounds are incidental, and they’re used to create spaces for a wider engagement with people in places. First there are foxes chased high into the scree of precipitous mountains. It’s fine, evocative stuff from the Wales of my imagination, but there are unexpected undercurrents at play. This is not the sneering, red-coated arrogance of a Home Counties hunt. Farmers have the final say; they suffer the hunts to happen on their land, even when they do not have leisure to participate themselves. And when the fox is run to ground, it is the farmer who decides if it can be bolted or killed. The hunt is a living, bugling expression of wealth and leisure, but farmers hold the whip.

His participation in the hunt puts Williams in a class above, but he is sure-footedly aware of the world beneath him. There’s a sense of social co-dependence here, and notes of a uniquely Welsh tradition, even as it fades towards the outbreak of the Second World War. This is not a watered-down facsimile of the English hunt; it’s something homegrown which runs parallel to the Lakeland footpacks and the ancient medieval traditions of the chase. Class becomes a prevailing theme, but there’s a mutual recognition between top and bottom which feels surprisingly equitable. As an officer in the Welsh Fusiliers, Williams finds fun in the rabble of Territorial privates in his charge; they’re all Welshmen, after all.

Later, Across the Straits describes a hunt for otters on the Welsh Marches. Williams’ sympathies lie squarely with an otter which is pursued so long and with such enthusiasm that it’s finally drowned. Years later, he is still ashamed to recall his part in the chase. It’s nothing like a moan or regret or a plea for forgiveness. It’s a frank, reflective account of what hunting can mean, right down to the complex and contradictory slew of emotions which can be evoked by “a kill”. And towards the end of the book, descriptions of grouse shooting across Pumlumon place a focus entirely upon other people and the roughness of the terrain.

It’s hard to place a spotlight on fieldsports because the objective is essentially dull and repetitive. Only children are fixated on the numbers killed and the quality of the shots taken. The real stories arise around the pursuit; how characters are organised and shuffled up by an engagement with a shared task. Williams seems to recognise this, and his gossipy, name-dropping style would work just as well if the book had been preoccupied with golf or horse racing. But sport is crucial here, because no other pastime calls for such a tight engagement with place. The book is old now, and it’s unlikely that any of the characters are still alive today. In that sense, it doesn’t matter who did what and where. The real story lies in a shared engagement with a countryside that is rich in wildlife, beauty and community. I allowed it to wash over me, skimming wherever the narrative slowed as the sun crept irresistibly across my office floor.

I tell myself that I do not have time to read properly nowadays; it’s often the root of my day’s frustration. But reading properly does not have to be followed by tests to review comprehension and recall. It can be rewarding to slavishly pursue a book against the grain; to blast it like a quarry’s face and then sift laboriously through the findings. But there is a different kind of reading which only calls for part of your attention. Across the Straits was the right book for my moment, and even if Williams’ Wales has vanished into history, it was a telling read for an idle day.

Leave a comment