I spent two hours at Rûg chapel in September. It was all the time I had to give, but the ripples have expanded outwards since them. It’s begun to feel like a vast period of my life, as if it were five years at school or the heights of an early marriage. Time warps, and the effect is usually to improve the complexion of memories; good things get better when they’re gone, and even the hardest loss will sweeten and proffer a kind of pleasure in the end.

I can’t deny it was a beautiful morning in Corwen. The lingering mist spoke noisily of autumn, and the orchards reeked of falling fruit. Beyond the visitor centre where I parked my car, the chapel itself was mine alone for almost an hour before others began to arrive. I approached it with caution, conscious that outside this tiny stand of shade and trees, the countryside ticked on without interruption. Pheasants stepped on the bare soil of autumn drills; woodpigeons clattered, and the roses fell.

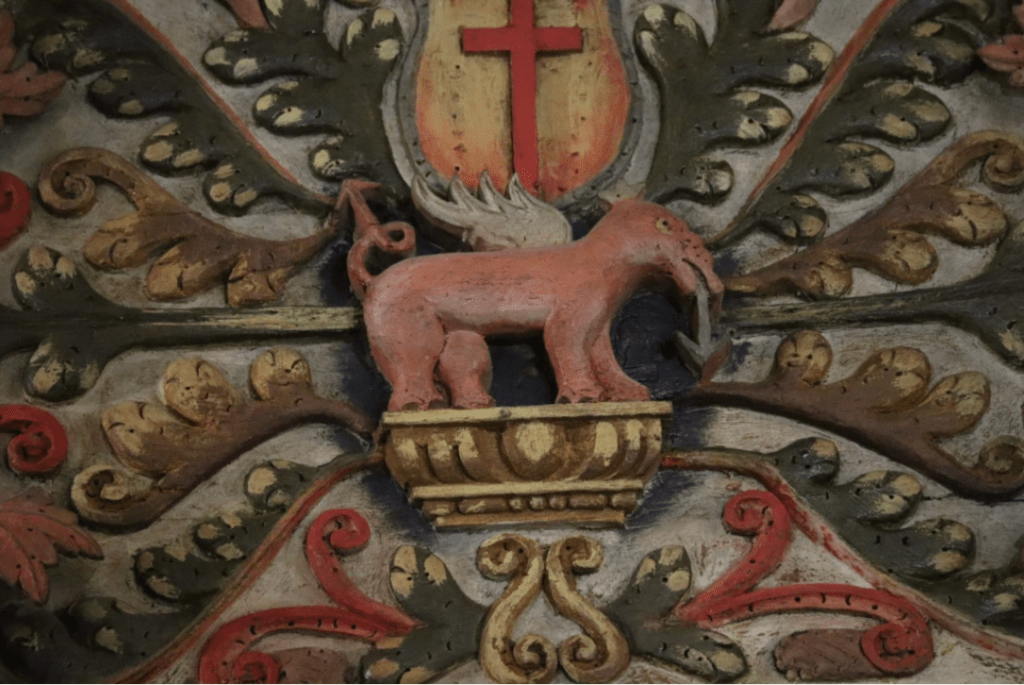

At first I sat in the pews and craned my neck to the ceiling. Then I climbed creaking steps to the gallery, enjoying the squeak and spring of ancient wooden boards beneath me. Upstairs was even better, and I came eye to eye with mythical beasts carved into a continuous frieze around the wall-tops. The chapel is vivid and rapturous from its roots to the rafters; the round-faced angels and the carved “bench ends” are explosively imaginative, but I didn’t have time to relax and absorb the detail. I was rushing on, and it became harder to gel with the place as it grew busier and more people arrived. But a sip’s as rich as a long, exhaustive pull, and now amongst all my channering recollections of that day, there are puzzles to play at.

The decorations at Rûg tickle me because they’re so obviously linked to the people and the community which made them. If (to my eye) there are inaccuracies and failures of realism, they’re explained by a sense of style – and the keyword here is “vernacular”. On this significant word, even just a quick search took me to a page about vernacular art in relation to “folk art” and “naïve art”, and how while these words literally mean “art produced by people who did not go through formal training”, they all confer distinctive meanings.

“Folk art” is produced by the people for the people. In that sense, it carries a functional sense of art that is designed to dosomething rather than be something. “Naïve art” suggests a rudimentary effort by a maker who was doing their best within the confines of a wider ignorance. For that reason, you could say it’s the most patronising variant; grinning stupidly, the yokel carpenter looks up from his carving and exclaims “I fink I did an art”!

But “vernacular art” is perhaps most neutral, because it seems to describe output created as a compromise between local style, taste and character. It’s a statement of geographical preference, if not originally through choice or selection, but through patterns established by repetition. I think vernacular art is fascinating because it encourages me to reassess the norms of my own cultural expectations. I see angels as beautiful, blond-haired men and women with soft, austere faces and flowing white gowns. That’s a norm established by the Victorians, so I am challenged by Rûg chapel’s 16th Century representations of angels as tubby, gaudy figures with dish-faces.

Vernacular religious art is rich because the subject matter does not change; each maker puts a new stamp upon it by imagining it differently. It’s hard to guess how individual vernacular “styles” emerged in the first place. Are makers responding to an original variant, or is it more like Chinese whispers, where each iteration of a symbolic truth takes you gradually further and further away from what it was meant to be? The poorer and more “naïve” the craftsmen or artists (here I am using the word “naïve” in a negative sense already), the bigger the margin of error between the whispers – there’s simply a deficit between what people are aiming for and what they’re able to deliver. Before you know it, multiple traditions have emerged.

In this sense, it’s interesting to remember how, in preReformation religious artwork, there do seem to have been censors attempting to steer the representation of religious symbols… the big-headed Celtic Jesus was frowned upon by the centralised church, which clearly held a certain standard and could not tolerate completely wildcard stuff from any old Herbert with a chisel. So a lot of vernacular religious art must have been a compromise between local taste, financial budget and centrally managed control. There would also have been certain leeway for monsters and demons, because nobody knew what they really looked like anyway. You can’t be accused of portraying a dragon inaccurately, and within that leeway, the cuddly pink elephant with white wings at Rûg is only a dragon because it’s more like a dragon than anything else.

However, we shouldn’t think of “folk”, “naive” or “vernacular” art as something bad or lesser. Knowing how hard it is to make anything, at the very least this work deserves to be recognised as complete (even down to the literal “completion” of being finished…) While much of this untutored, unbounded creativity is simpler than more “advanced” art forms, it’s still landing punches. It works, and when mounds of vernacular art are swept together like fallen leaves to decorate a chapel like Rûg, the effect is intoxicating. It’s no wonder that I am still trying to make sense of it.

Leave a comment