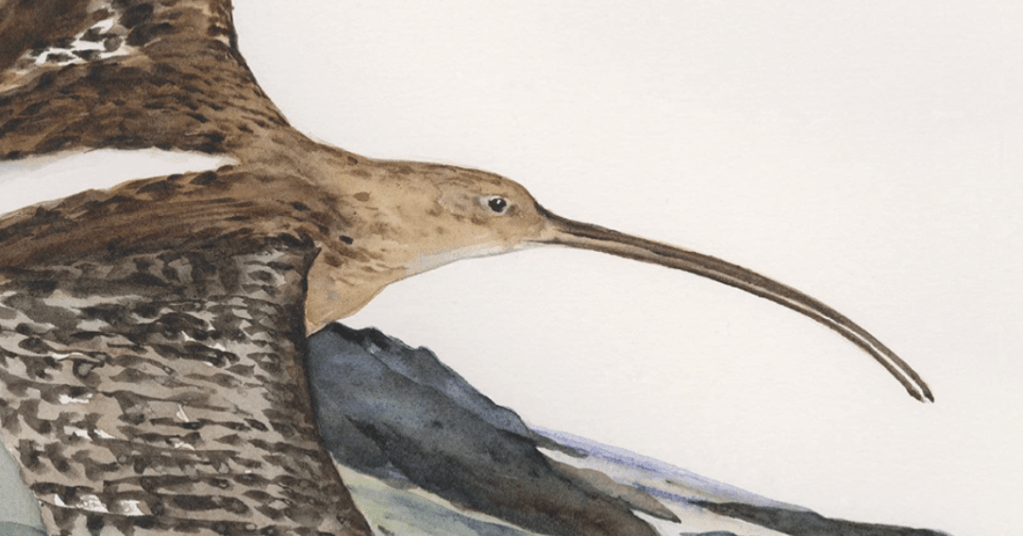

Tom Bullough’s Sarn Helen follows the author’s journey upon the ancient roman road which ran from south to north across Wales, from Neath to Llandudno. Gripped by an ever-heightening sense of of Cymruphilia, I would have found it hard to walk past this book, particularly since it’s got a picture of a curlew on the front cover. That’s clearly a trigger for curlew enthusiasts like me, but curlews have considerable reach beyond their immediate devotees. They’re everywhere at the moment – James Rebanks’ 2021 book English Pastoral has a curlew on the cover, even though the author would have preferred a barn owl. But final decisions on cover design are made by marketing teams who carefully monitor trends and patterns. Curlews trump barn owl nowadays.

Sarn Helen has got almost nothing to do with curlews. The birds feature as just one of many declining species in a wider landscape, and aside from one passage related to curlew conservation conducted by the RSPB, the birds appear here and there as symbolic figures in hagiographies. Away from the specific species, this book takes a far more holistic approach to climate change and biodiversity loss, viewing both as part of a global ecological collapse. Ancient myths and fables are finely balanced against visions of suburban streets and post industrial grime. At one point, the story of a hunt for the enchanted boar Twrch Trwyth across the primordial wildwoods of Wales is measured against a grim, modern reality of Suzuki Vitaras and robotic lawnmowers “creeping carefully around their gardens, ensuring an aesthetic for no one to appreciate”. It’s an eye-widening juxtaposition, and likewise in the fading presence of birdsong, the rumbling sterility of aircraft noise becomes a terrifying motif.

Sarn Helen charts a gradual accretion of cultural continuity. Reading this book, it’s possible to understand how we got from the Roman invasion to the Second World War. The story gathers pace and complexity, but it’s always comprehensible as a single, coherent narrative. However, the book is effective because it shows how that story has been overcome by a system of abrupt wobbles in recent years; the collapse and the departure from that ancient tale. Sarn Helenis concerned with a nation on the brink of closure, and that’s extremely jarring. Stories of myth and legend from early and pre-Christian times are offered as a kind of Creation Myth, and readers are invited to conceive of Destruction Myths.

We’re used to scare tactics from climate activists. We’re told to change now or we’re doomed. I don’t know whether to read Sarn Helen as more of the same, and perhaps we’re all getting numb to warnings screamed through megaphones. We were being told to “change now or we’re doomed” ten years ago, but most people find the reality of this modern apocalypse is strangely comfortable. If you can ignore the latest announcement of extinction or collapse, the end of the world does not seem that bad. It’s usually happening somewhere else, and it goes away when you turn your back on it – so it’s not surprising that many people feel it’s not urgent. But there has to be a rubicon, and maybe that’s where Bullough stands, because it may already be too late to save the world. This book veers scarily close to that fatalistic conclusion, which it offers as realism. But if we really are beyond the point of no return, how does that inspire us?

I like to think that I’m doing my best by the world. I don’t have a lavish, jet-setting, consumerist lifestyle, and nine tenths of my income is derived from conservation work. I don’t doubt that I could do more, but I also recognise that I currently do more than most people I know. If climate activists stand on a spectrum, then I am already quite near Tom Bullough in much of what I do. I would not join him on an Extinction Rebellion demonstration, but I do plough years of my life into habitat restoration and species recovery. It would be unhelpful to fall out over the best way to respond when most people are not responding at all, but is my time better spent on conservation or in police custody after demonstrations at the Houses of Parliament? That’s an open question. I don’t know the answer.

I agree that it makes sense to unite spirituality with conservation, and that nature demands a degree of reciprocity which western societies refuse to accommodate. But sensing that Sarn Helen is directed towards an audience of similarly conscientious readers, it’s hard to imagine what the book can do beyond exciting further stress and anxiety among people who are already trying their best. Inside the book, the Jackie Morris illustrations feature stylised vignettes of birds and celtic motifs. This artwork will doubtless be sold in its own right to people for whom nature and spiritualism is a rising trend, but outside these comfortable homes, what’s next? I agree that there is a problem, but I’m not sure that Tom has the only solution. It’s a deft and cleverly written book, but it’s hard to imagine how Sarn Helen will charge the groundswell of change required to save the world.

Leave a comment