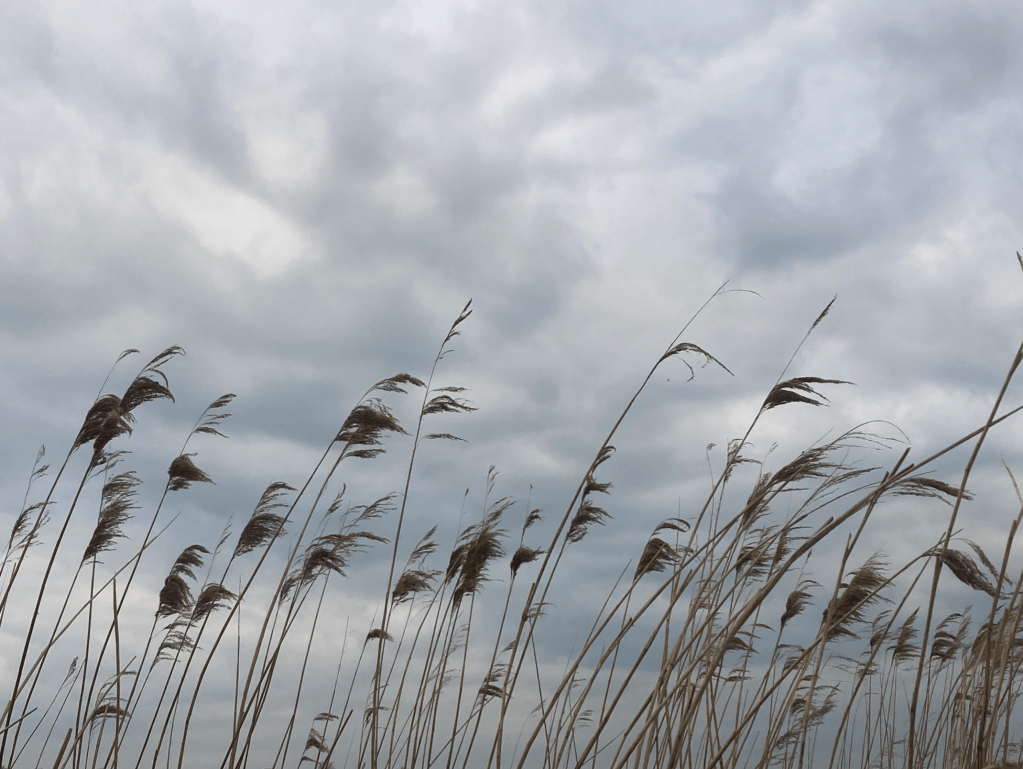

The sun sank into the stifling, house-tall reeds. All the warming day I’d held my peace on the tarmac road until I fell at last to stop on the Somerset Levels. I was down in the outrageous south, in sight of Glastonbury Tor, struck and sickened with premature summer in the last week of April. I rolled from the car and sat in the verge, smelling the resurgent rot of roots in tepid water.

Then beneath the skim of low-flying ducks and the early willow down, the sound of a bittern came into me like the groan of heavy furniture a floor or two below me. I’m glad I saved this sound for now and didn’t rush to hear it a decade ago. I’m only just big enough to bear it, and I heard in that open call those rich and mingled associations of the fen; the Anglians wading half-seen and steamily on stilts; Alfred forced to hide in the marshes and lick his wounds as Guthrum ran riot across Wessex. Here’s the backdrop sound to a thousand old stories, and newer too from Frodo in the Mere of Dead Faces to Howland Reed and the deal of the Crannogmen.

They’re not my stories, but fens like these leave lasting stains in the imagination. Whatever we used to call fens in Galloway have all been drained away now, but you can still find them on old maps. And it doesn’t matter that I cannot place my finger on a specific memory that brings that old world close to mind, because in the warm insipid water and the gathering gloom, there’s something universal in these amniotic Levels. It’s a sound of sleep and prebirth; miasmic recollections of a time before you ever lost or a knew a thing, and you were held apart from the world by an inch or two of warmly sodden hide.

I thought of that essay called Mossbawn by Seamus Heaney, in which he remembered the sound of the waterpump in the farmyard of his childhood home. He throws a shape around that sound, naming it to evoke the liquid swell of water rising in a pipe. He called it omphalos; the navel; root of our word umbilicus. That pump is his beginning; a start that harked for him just as this sound drew me back to memories I’ve never had, and hearing this at thirty six, I understand now why it is that when you run a bath, you have to stir the waters as they’re drawn; otherwise they’ll lie in layers and shock you.

You can try and call it birdsong and the simple booming of spring in the marshes, but I cannot vouch for that sound which slipped like mucus in the reed roots. And I’d use Heaney’s word to feel again how very young we are.

Leave a comment